SHORT

EXPLANATION:

Provided by:

Bob Campbell

Bounty Land Warrants for Military

Service in the War of 1812

After the War of 1812, Congress

enacted legislation to reward military service by entitling veterans to

claim land in the northwest and western territories. This so-called

"bounty land" was not granted outright to the veterans, but

was instead awarded to them through a multi-step process beginning with

a bounty land warrant.

Bounty land warrants weren't

automatically issued to every veteran who served. The veteran first had

to apply for a warrant, and then, if the warrant was granted, he could

use the warrant to apply for a land patent. The land patent is the

document which granted him ownership of the land.

Basically, the warrant is a piece of

paper which states that, based on his service, the veteran is entitled

to X number of acres in one of the bounty land districts set up for

veterans of the War of 1812. These land districts were located on public

domain lands in Arkansas, Illinois and Missouri.

The warrants, themselves, were not

delivered to the veterans; all the veteran actually received was a

notification telling him that Warrant #XXX had been issued in his name

and was on file in the General Land Office.

Prior to 1842, if a veteran chose to

redeem his warrant for land, he was required to choose land in one of

the three states listed above. (After 1842, he could redeem his warrant

for public lands in other states.)

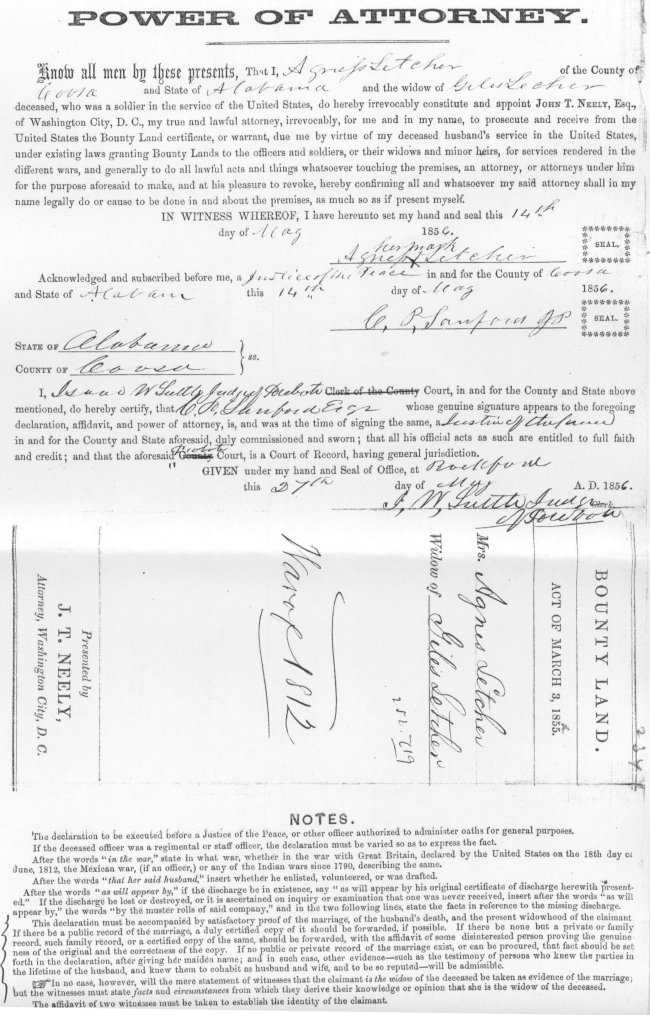

Warrants could be assigned or sold to

other individuals.

Benjamin Hibbard, an American public

lands historian, believed that the government chose to set the land

districts up in these frontier areas because they thought it would be

really nifty to have a few thousand battle-hardened war veterans &

their families acting as buffers between established settlements and the

Native American population. For good or for ill, the veterans were too

smart to fall for that one, and most chose to sell their patents to land

speculators. So keep in mind that, even if your ancestor applied for a

patent, he may never have set foot on his land.

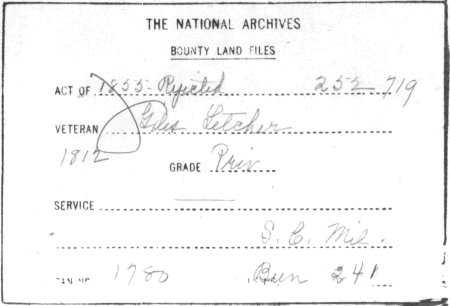

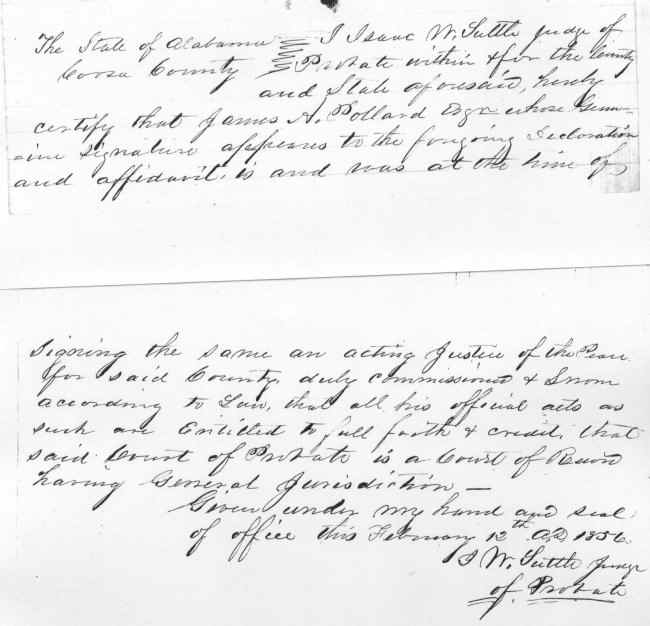

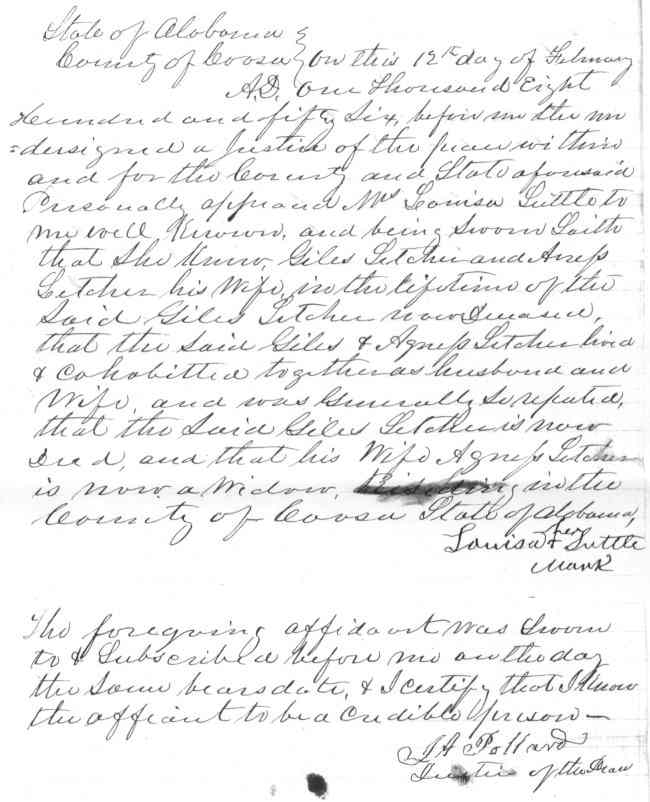

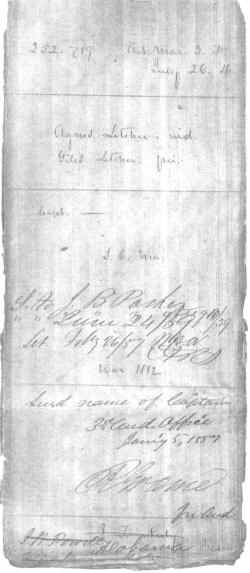

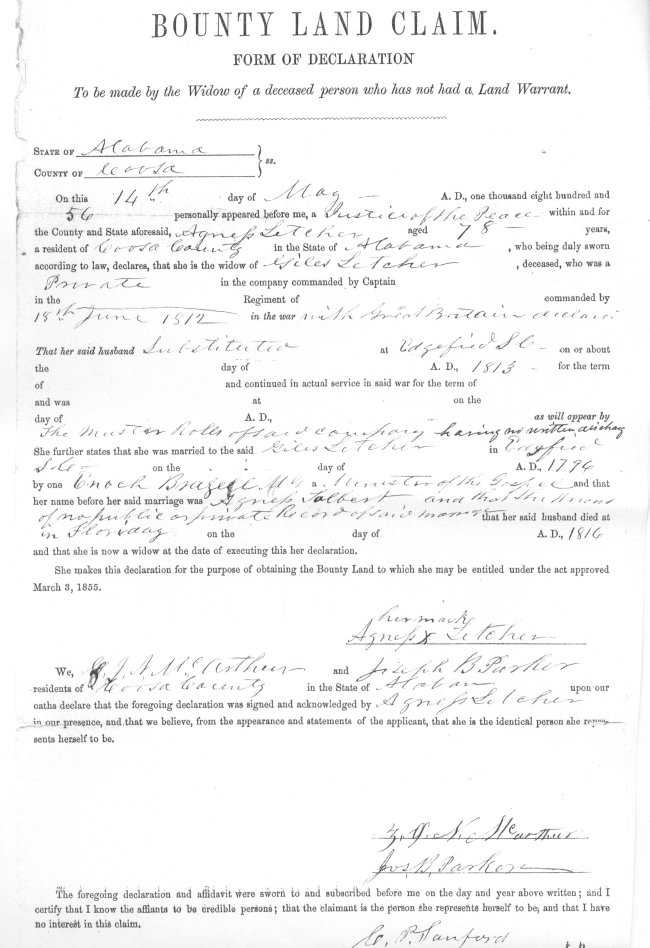

The Bounty Land Warrant File

A veteran who decided to redeem his

warrant was issued a patent for the land itself, and a "Bounty Land

Warrant File" was created in the General Land Office. This file

contains the surrendered warrant, a letter of assignment (if he assigned

his interest to another party) and any other documents pertaining to the

transaction. The warrant itself should include the name of the veteran,

his rank on discharge, his branch of service (including company, etc.),

and the date the warrant was issued. It may also include the date

the land was located and a description of the land.

If he obtained bounty land, you should

be able to find your ancestor in National Archives Microfilm Series M848

(14 rolls), War of 1812 Military Bounty Land Warrants, 1815-1858.

This series includes an index to patentees in Missouri & Arkansas, a

partial index for Illinois, and an index for patentees under the 1842

act (the one that allowed them to choose lands in areas other than MO,

AR & IL). If you find that he patented his land, and you want more

information than is contained on the microfilm, you may be able to

obtain it by writing the National Archives and having them search the

General Land Office abstracts of military bounty land warrant locations.

LONG EXPLANATION:

The term bounty land is

somewhat self-explanatory. Tracts of land were given outright by the

states, and later by the federal government as partial compensation (or

"bounty") for service in times of military conflict. Such

bounty was also occasionally used by the government to incent men to

serve in war or conflicts. Bounty land warrants were issued from the

colonial period until 1858, when the program was discontinued, and five

years later, in 1863, the rights to locate and take possession of bounty

lands ceased.

There were a number of different acts, over an 80 year period, which

provided for the issuance of bounty land warrants. One of the earliest

was the Congressional Act of 16 September 1776, which was an inducement

to join the Continental Army, and which provided from 100 to 500 acres,

and was dependent on the rank attained while in the Army. In later wars,

other acts provided for different types of warrants for enlisted men and

officers.

The great bulk of early bounty land at the time of the Revolution was in

Virginia, as it existed in colonial times. Since Virginia provided the

great bulk of fighting men in the Revolution, the first bounty lands

were to be located between the Mississippi, Ohio and Green Rivers in

what is now Kentucky. However, this area did not provide enough land,

and the Virginia Military Tract was established, which was in what is

now the state of Ohio. Continental Army soldiers from Virginia were the

only group allowed to settle in the Ohio area, while state soldiers were

to use the lands in Kentucky.

We must remember that bounty lands were given by both the state and

federal governments. As might be expected, state bounty lands were

almost always within the state lands governed by that state, while

federal bounty lands were in specified districts and some federal land

states. The Congressional Military Tract was established in 1796 in

Ohio, and was set up in five-square-mile townships, rather than the

usual six mile arrangement. A quarter-township(4000 acres) was the

minimum that could be purchased or "redeemed". Federal bounty

land warrants were normally for only 160 acres, however, which worked a

hardship for individual claimants, causing them to have to band together

as groups in order to obtain such high acreage. By 1800, parcels holding

as little as 100 acres were being offered.

The War of 1812 saw the bounty land process offered again as an

inducement to bring men into the military. Congress created three new

military districts to handle the future redemptions of new soldiers. One

was in Illinois, one in Michigan and one in present-day Arkansas(then

Louisiana). However, lands in Missouri were later substituted for those

in Michigan, due to the undesirable nature of the land in Michigan that

had been set aside for this purpose. Other later acts of Congress, until

1855, continued to address the needs of soldiers wishing to redeem their

bounty land warrants and efforts continued to try to provide suitable

land area for these soldiers.

What records are available to the genealogist who is trying to determine

if an ancestor received a bounty land warrant, and if so, what might be

found in the records? The most comprehensive and complete record of such

warrants is contained in the National Archives in Record Group 15, Federal

Bounty Land Applications. The records contained in this group range

in time from the Revolution to the year 1917. Pension files, as well as

bounty land records, are contained in this group. Bounty land

applications for the Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War

are in this group, and there are some other case files covering the

period 1814-1856. A tragic fire some years ago destroyed thousands of

bounty land warrant application for the years from 1789 to 1800. If your

ancestor applied in this period for bounty land, the original documents

may be lost, although some abstract information still exists on these

earliest applications. There are also registers for bounty land warrants

and for claims which run up until 1912. Although the ability to claim

bounty land legally was stopped in 1863, there were civil suits and

other litigation which caused some lands to be granted as late as 1912.

Other important research references include the Index of

Revolutionary War Pension Applications in the National Archives,

which was prepared by the National Genealogical Society, as well as the

very useful and popular Genealogical Abstracts of Revolutionary War

Pension Files by Virgil White.

When looking for state bounty land warrants associated with the State of

Virginia (where, as noted earlier, the greatest bulk of these will be

found), the genealogist should make use of Record Group 49 in the

National Archives, which has about 16 different components contained

within it, such as the warrants issued under each act, treasury

certificates, exchange certificates, scrip records, and others. The term

"scrip" basically means the issuance of paper

"scrip" certificates that could be used in any land office,

and were exchanged for Virginia military bounty land warrants.

Another valuable reference work is the Federal Land Series by

Clifford Neal Smith. There are also numerous compilations that are now

available that list claimants by land office. There was a land office

established for each federal district, and, as the population grew, the

districts were subdivided and more land offices were established to

handle the overflow.

It is interesting note that, insofar as Revolutionary War bounty land

claims are concerned, the majority of these were redeemed, except for

Ohio, in Iowa, followed by Wisconsin. When searching for bounty land in

Ohio, the Index for Federal Land Entries, circa 1802-1849,

published by the Ohio Historical Society is often useful, although the

Symmes Purchase, the Connecticut Western Reserve and the Firelands are

not included.

In sum, the business of bounty land became a very large enterprise in

the United States for nearly a century. Although warrants could be

assigned by the original applicants, the original applicant was required

to apply for the warrant before assignment could occur. There were firms

established for the sole purpose of handling bounty land warrants for

applicants.

The genealogist should also be aware that there is some bounty land

warrant information available in the form of Canadian Refugee Warrants

and Canadian Volunteer Warrants, which cover those Canadians who were

"refugees" from Canada and assisted the American efforts

during the Revolution, and those Canadian volunteers who served during

the War of 1812. These records are held by the National Archives. Of the

two types, the Volunteer Warrants generally provide more information.

For more detail on Bounty Grants

click on the following links:

http://www.ultranet.com/~deeds/bounty.htm

|